oCD treatment in sydney

why do i keep checking things over and over? Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD)

What is OCD?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a well-recognised but debilitating mental health condition that is linked to intrusive, obsessive thoughts (thinking repetitively about distressing things), and compulsions (needing to do certain things in a certain way). These intrusions and compulsions significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, and often negatively impact work and social life. While OCD comes with a lot of anxiety, OCD, since 2013, is not classified as an anxiety disorder. If you think you or someone you know could benefit from treatment, our psychologists in North Sydney offer OCD treatment in Sydney.

Table of Contents

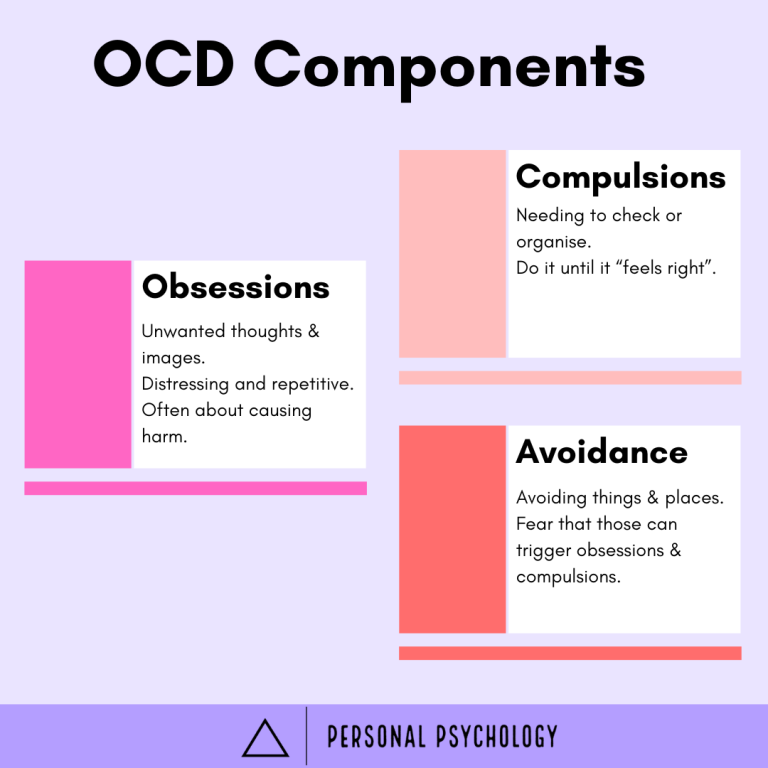

The Three Components of OCD

OCD is characterised by three primary components. First, individuals experience obsessions, defined as intrusive and unwanted thoughts, images, or ideas that often revolve around specific themes, often horrific or blasphemous images, thoughts of contamination, or being uncertain about completing certain actions, such as locking the door. The second component involves compulsions, which are specific behavioural actions (doing things), verify actions (checking things), or covert mental rituals (thinking about things until it feels just right). Actions are used to neutralise the negative feelings associated with the obsessions. Additionally, individuals with OCD engage in extensive avoidance behaviours, such as not going to places or not doing certain things, to prevent the provocation of obsessions and subsequent compulsions.

Living with OCD often causes a serious burden to people with the condition, and often people around them as well. The complexities of OCD require effective treatment methods to help the person suffering from symptoms to regain at least some, sometimes all of their control over their thoughts and actions. For those seeking support, accessing professional OCD treatment in Sydney can be a crucial step toward managing symptoms and improving quality of life. Skilled therapists and evidence-based approaches, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP), are widely available in Sydney to provide tailored support for individuals struggling with OCD.

What does ERP stand for – the roots of Exposure and Response Prevention

CBT therapy has emerged as the most effective psychotherapeutic method for treating OCD. Exposure with response prevention (ERP), a subset of CBT, is the first line treatment for OCD treatment. The core principles of ERP were defined in 1966 (Meyer). While the treatment went through refinements since then to address the diverse presentation of OCD, the core ideas remained the same. ERP is personalised by the therapist to address the diverse symptoms of OCD, which sometimes include aggressive obsessions, checking compulsions, symmetry obsessions, ordering compulsions, contamination obsessions, cleaning compulsions, and even hoarding.

The presence of comorbid conditions, especially other anxiety disorders and depression, present further complications to the treatment of the disorder, and need to be addressed during therapy.

Challenges in OCD Treatment in Sydney

It is estimated that more than 150,000 people live with OCD in Sydney, making treatment difficult to access.

The wide variety of OCD symptoms make it difficult to apply a one-size-fits-all treatment plan. Mental obsessions and intrusive thoughts (rather than just behaviours) often require more therapy sessions due to their chronic nature, as behaviours are generally easier to control than thoughts. Other symptoms, such as contamination fears, may be challenging to treat when they are paired with disgust, which has different response patterns to exposure than anxiety.

How does ERP work for OCD?

ERP is a structured treatment that’s primary goal is to expose individuals to their OCD fears in a controlled, systematic, but approachable manner, making the progress neither too easy, nor too hard for the individual. The treatment process involves creating an exposure hierarchy of feared objects or situations, ranging from the least anxiety or fear provoking (level 1) to the most distressing (level 10). Clients are then gradually exposed to items on this hierarchy, typically starting around level 3 or 4, working up to level 10.

Apart from exposure, the treatment also requires response prevention, in other words the client must refrain from completing compulsive behaviours that would neutralise or alleviate anxiety or distress. For example, if they feel they need to check the door again to make sure it is locked, they must resist actually doing it, even if it causes distress. If a client ‘slips’ after completing a level and gives in to the urges, re-exposure to the fear stimulus is recommended as soon as possible.

Numerous studies have shown the efficacy of ERP for OCD. The method of delivery is crucial, however, with therapist-controlled in vivo ERP (completing tasks in the real world) with imagery (imagining distressing situations) showing the most significant symptom reduction. Response prevention is also more effective when complete rather than partial, as in, not buying in at all to the behaviours rather than stopping right before completing the action (not even walking to the door to check the lock). Exposure in vivo paired with therapist-developed imagery had a substantial effect on depression reduction in OCD clients as well, often a problem for people presenting with the condition.

Why might ERP fail?

ERP must strike an approachable balance between activating the fear and anxiety without overwhelming the client. Too fast progression up the exposure hierarchy may lead to excessive emotional arousal and prevent learning (habituation) that the fear can be tolerated; in some cases, if the exposure is extreme, it may lead to early termination of treatment. Clients often engage in avoidance or “safety behaviours” to reduce the distress, but it also reduces the effectiveness of the exposure. Clinicians must monitor these to optimise treatment benefits, as treatment only works if clients fully face their discomfort and allow their nervous system to process the distress (habituate).

Many individuals with OCD perform covert rituals that require specialised attention during ERP. A covert ritual may not be obvious to the clinician or others but is aimed to reduce the distress. These include repetitive thoughts or small muscle movements to neutralise the distress. The client must be honest about these and work with the clinician to avoid these, otherwise treatment will be unlikely to succeed.

If the client with OCD struggles with depression as well, they may experience low motivation for ERP, making treatment more challenging. Sometimes targeting the low mood first, then resuming OCD is recommended.

While most OCD clients recognise their irrational thoughts, some clients may express overvalued ideas, whereas their obsessions are considered essential rather than irrational. This belief can interfere with ERP, and in some cases, render it ineffective. Challenging the necessity of these thoughts is critical before resuming treatment.

Strict adherence to treatment, including completing homework exercises, predicts both short and long-term outcomes. Explaining and getting a commitment to regular attendance to sessions and completing homework is critical to the therapy’s success.

effectiveness of ERP for OCD

Attrition rate during treatment using ERP is substantial, typically between 11.4% and 18.4% of clients not completing the full treatment. While this sounds high, the dropout rate of ERP is similar to (not statistically different from) the attrition rates in other treatment options, such as cognitive therapy.

Interestingly, treatment experience, the qualifications of the therapist, and the number of treatment sessions are not good predictors of the dropout rate for ERP. In other words, some clients would find ERP acceptable and complete treatment, and approx. 1 in 10 just do not find it tolerable or useful, irrespective of the context it is delivered in.

Is ERP for OCD hard?

The evidence behind the efficacy of ERP for treatment for OCD is substantial. However, some with OCD feel that ERP can sometimes be “psychological punishment”. ERP essentially requires patients to confront their fears and anxieties repeatedly, in length, until they become desensitised to them, and their intrusive thoughts lose their grip.

ERP therapy process, however, may feel like a cruel desensitisation treatment, filled with “pain and misery”, as some label it. While the data shows its benefits, it’s hard to deny that this treatment approach can seem disheartening, leaving patients feeling as if they need to willingly enter a state of emotional agony for long periods in the hope to get better.

Furthermore, some argue that ERP can feel too fast and too extreme for certain people, causing extreme anxiety, and making the process unbearable, leading to dropout and dissatisfaction with treatment. While there’s a huge base of ERP advocates, it is important to remember that ERP may not be a one-size-fits-all approach to OCD treatment.

How long does it take for ERP Therapy to help OCD?

It usually varies case-by-case, as with most psychological disorders and interventions. However, broadly speaking, substantial gains can be achieved within 15-20 sessions, if the client is motivated to change, the therapeutic alliance between the client and therapist is good, and OCD mostly affects behaviours rather than thoughts.

For children and adolescents and mild to moderate cases, generally 12-20 sessions are needed. For adults with similar presentations, 12-16 sessions.

Contamination fears with OCD typically require more sessions, with both adults and children and adolescents needing more than 20 sessions.

Checking behaviours are generally easier to manage, and clients see benefits between 12-16 sessions in mild to moderate cases.

Hoarding, a special type of OCD, tends to be more treatment resistant, with individuals needing at least 24 or more sessions to manage their symptoms.

The need for ERP alternatives

CBT and ERP

A common agreement among those with OCD is that ERP works, but it’s a gruelling process that at times feels like “torture”. This prompts questions about whether there are any other viable or prominent treatment options for OCD. Understanding both points, namely that ERP might be too difficult for some, but also considering that living with OCD can be an unrelenting struggle, there is a definite need for alternative options.

ERP, and its close cousin Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), have shown to be effective for many. Still, the journey with OCD is unique for everyone, and what works for one may not work for another. As seen from personal accounts, while ERP or CBT may have been effective for childhood OCD, they might not provide the same relief during adulthood or a severe relapse.

Medications

OCD sufferers often find relief in medications, which can alleviate at least some of their symptoms. However, these, too, come with their challenges, and finding the right medication can be a trying experience Trialling various options like escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), bupropion (Wellbutrin), or lorazepam (Ativan) can feel like a shot in the dark, sometimes without any benefits, but with very real side-effects.

In some cases, the medication that might work can also become a source of fear over time, as individuals may develop an irrational fear of taking them. This additional exposure to anxiety, induced by medication, can be frustrating, or sometimes debilitating, emphasising the complexities and challenges involved in OCD treatment.

Psychedelics and OCD?

One of the emerging alternative methods gaining attention is the use of psychedelics (drugs, such as magic mushrooms, that can make you see, feel, or experience things that are not part of everyone’s daily reality). They often alter your perception, thoughts, and feelings, sometimes leading to vivid and unusual experiences, such as hallucinations, deep introspection, and a heightened sense of connection to the world. Popular examples of psychedelics include LSD, magic mushrooms (psilocybin). Some individuals have reported substantial progress in ERP using psychedelics, which may facilitate neural plasticity and disrupt deeply ingrained and longstanding thought patterns, especially in the case of adults. These experiences vary, with some achieving spontaneous and substantial improvement, while others find long-term benefits through repeated use.

However, it is essential to be cautious about using psychedelics. Not only are they not legalised in many countries, but they also have undesirable and not yet well understood side effects, especially with the combination with traditional pharmaceuticals. Many prescription antidepressants, such as SSRIs and MAOIs, can interact unfavourably with psychedelics, making it risky to use them concurrently, or even within weeks of each other.

To address these concerns and offer a more structured and supervised approach, some clinics guide patients through psychedelic therapy, providing a safe, legal, and monitored environment for this unconventional treatment. This approach has shown promise for those who are hesitant about less regulated substances, despite its substantial cost and limited availability in many countries.

Another psychedelic, ayahuasca (made from the plant Banisteriopsis caapi), is started to emerge as a potential treatment for OCD. While ayahuasca is considered a powerful hallucinogenic substance and typically used ceremoniously, it might have benefits for some individuals dealing with OCD. However, there is not enough research on ayahuasca and OCD, and it is important to approach this topic with caution.

Cognitive Therapy for OCD: Unhelpful thought patterns

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), and importantly its cognitive part (Cognitive Therapy, CT) for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) targets thoughts, beliefs, and their influence on behaviour. The theory behind it is that irrational thoughts lead to problematic behaviours, so this therapy offers a unique perspective on tackling OCD through changing thoughts (rather than desensitisation, which is the core of ERP).

Cognitive Therapy takes inspiration from ancient philosophy, namely that nothing is inherently good nor bad; it’s our interpretations and judgments that make them so. The core principle of cognitive therapy is to identify and change the unhelpful labels (appraisals) of intrusive and irrational thoughts and symptom-related beliefs, such as that “urges are bad and we must do something to neutralise them”, and gradually replace them with more adaptive thoughts (“urges are unpleasant but I can deal with them”).

What is the hardest type of OCD to treat?

A cognitive process termed “inflated responsibility” is often the primary target of cognitive therapy — the irrational thought that “this is me who must do something about my thoughts”. According to the theory, inflated responsibility plays a crucial role in how individuals with OCD appraise the significance of their thoughts. Experimental studies support this model, showing that perceived responsibility is directly related to the intensity of checking behaviours.

Despite the theoretical support for targeting inflated responsibility through cognitive therapy, most OCD sufferers have different types of labels (appraisals) of intrusive thoughts and beliefs that go beyond inflated responsibility. It is thought that Primarily obsessional OCD (also called pure obsessional or pure-O) might be most treatment resistant (hardest to treat). With this condition, the intrusive thoughts revolve around doing things that are unthinkable for the person, and under normal circumstances would never act on these thoughts, such as yelling out obscene things, hurting someone, or intentionally causing an accident. Cognitive therapy is the primary intervention for Primarily obsessional OCD to help the client manage these often absurd thoughts.

Some common beliefs include overestimation of threat (If I don’t do this, something terrible will happen), overimportance of thoughts (thoughts are essentially the same as actions), intolerance of uncertainty (I must know what will happen), importance and control over thoughts, and perfectionism. These beliefs are central to cognitive therapy of OCD, and their variability poses substantial challenges to both the therapist and the client.

Combined treatment, better results?

While cognitive therapy for OCD has a shorter history compared to Exposure with Response Prevention (ERP), research suggests that it is indeed effective. It would seem logical that combining the two (ERP and cognitive therapy) would yield almost double the results, but studies have suggested that the combination therapy may only lead to small and non-significant benefits in symptom reduction, even if separately they both work well.

While there is some evidence showing that cognitive therapy may work for OCD, for the time being it is not the recommended standalone first-line treatment. Instead, it might be a good idea to combine ERP and cognitive therapy to optimise changes in symptom-related beliefs, distress tolerance, adherence to treatment, and, importantly, reduce dropout, which is substantial in the case of ERP.

Overview of OCD Treatment

ERP is considered the first line, most evidence-based psychological intervention for OCD. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has some evidence behind it as well, although it is a newer type of intervention for OCD with less research support. Cognitive therapy is recommended to be administered in combination with ERP to address the complexity of many OCD symptoms, including substantial irrational thoughts. Cognitive therapy with ERP can aim to address and modify the OCD-related fears and underlying irrational thoughts that maintain some of the symptoms and behaviours of the disorder.

There are some well-known limitations of treatments of OCD, most notably treatment adherence issues (not completing exercises between sessions, not attending sessions regularly), dropouts (discontinuing therapy altogether), and challenges in treating certain symptoms of OCD, such as checking behaviours, and sexual or religious obsessions. Apart from these challenges, unfortunately, many individuals with OCD do not even seek treatment.

Regarding thoughts and behaviours, there might be a bidirectional relationship between cognitive therapy and ERP, where changes in thinking patterns may lead to changes in behaviours; at the same time, exposure leads to lowered fears and anxiety, making the distinction between thoughts and behaviours (or types of treatment) less critical.

It is a good idea for the clinicians to verify the completion of homework and exercises at the beginning of each session, as adherence to treatment protocols is essential. Some clients might show resistance due to inflexibility of some of their irrational beliefs, intolerance of stress that ERP might bring on, extreme risk aversion. In these cases, cognitive work can help to address some of these concerns and increase adherence.

Typically, the worse the symptoms are, the more intensive treatment is required, and in some cases, therapist-assisted exposure (rather than individual homework exercises) are needed. Having said that, online, internet-delivered cognitive therapy might work well for some patients, especially for those whose presentation is less severe and otherwise cannot access treatment in person.

Challenges in OCD Therapy

While the evidence behind Exposure with Response Prevention (ERP) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for OCD is convincing, a lot of challenges can and do come up, which may impact the success of the intervention. These challenges encompass the limited number of qualified therapists, the demands of ERP and cognitive therapy put on patients, the importance of the therapeutic alliance between the clinician and the patient (clients need to get along with and trust their clinician), and the sometimes treatment-resistant OCD.

Therapist’s misconceptions, and Therapeutic Alliance

Delivering ERP and CBT, especially for clients with severe symptoms, is a demanding and often stressful task for clinicians and clients alike. Moreover, there are longstanding misconceptions about the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ERP, also affecting both clinicians and clients. Unfortunately, some clinicians downright refuse to deliver ERP or any other types of exposure therapies, claiming that it would put too much stress on the clients without any real benefits, despite the irrefutable evidence showing otherwise.

The success of ERP and CBT requires a strong therapeutic alliance, given the demands of these therapies. The client must trust the clinician, otherwise, they are unlikely to go through with the long list of anxiety and fear producing exercises. Therapeutic alliance also requires well-defined treatment goals, which is defined early on in therapy. Realistic and tangible goals (“I want to be able to manage my urges regarding checking behaviours”) are superior to vague or unrealistic ones (“I never want to feel urges again”). A particular challenge of therapeutic alliance is the frustration of the clients if symptoms are not getting better despite the intervention, often leading to dropouts rather than collaborative problem solving. Checking for early signs of frustration and dropping adherence may address this.

Resistant OCD Cases

Finally, it is important to mention that roughly 30% of OCD sufferers do not respond to any empirically based intervention, including ERP, CBT, or medications. The management of these resistant cases involves considering stepped care models, as suggested by the NICE guidelines, which recommend more intensive treatment, and involving a team-based, often multidisciplinary team-based approach. The research is, however, lacking on how to help people who had multiple failed interventions as it is often unclear what contributes to non-response.